From boom to balance: managing bettongs at Arid Recovery

Arid Recovery

28 October 2025

Burrowing bettongs are on the move at Arid Recovery. After growing populations inside the predator-free Main Exclosure, our team has relocated 141 bettongs to other parts of the Reserve where quolls now help keep numbers in check. The move is part of a long-term experiment exploring how native predators restore balance to arid ecosystems. Big numbers might sound like conservation success, but true recovery is about healthy, sustainable populations, and thriving landscapes.

This year our team has been carefully relocating burrowing bettongs from Main Exclosure to other parts of the reserve.

Why? Because at Arid Recovery, bettongs have a complicated history.

Burrowing bettongs have played a major role in shaping Arid Recovery’s journey. Reintroduced in 2000, their population increased from 30 individuals to more than 1,500 within 17 years. Without natural apex predators such as dingoes or quolls, the population continued to rise even during dry years, placing increasing pressure on the landscape.

As bettong numbers expanded, their favourite food plants like ruby saltbush and native plum declined significantly inside the Reserve while remaining healthy outside the fence. More than a quarter of all perennial shrubs showed browsing damage from bettongs. These were strong signs that the ecosystem was being pushed out of balance.

.png?lang=en-AU)

Bettongs have dug around a sticky hopbush (Dodonaea viscosa subsp. viscosa) (left) and desert rattlepod (crotalaria eremaea) (right) damaging them.

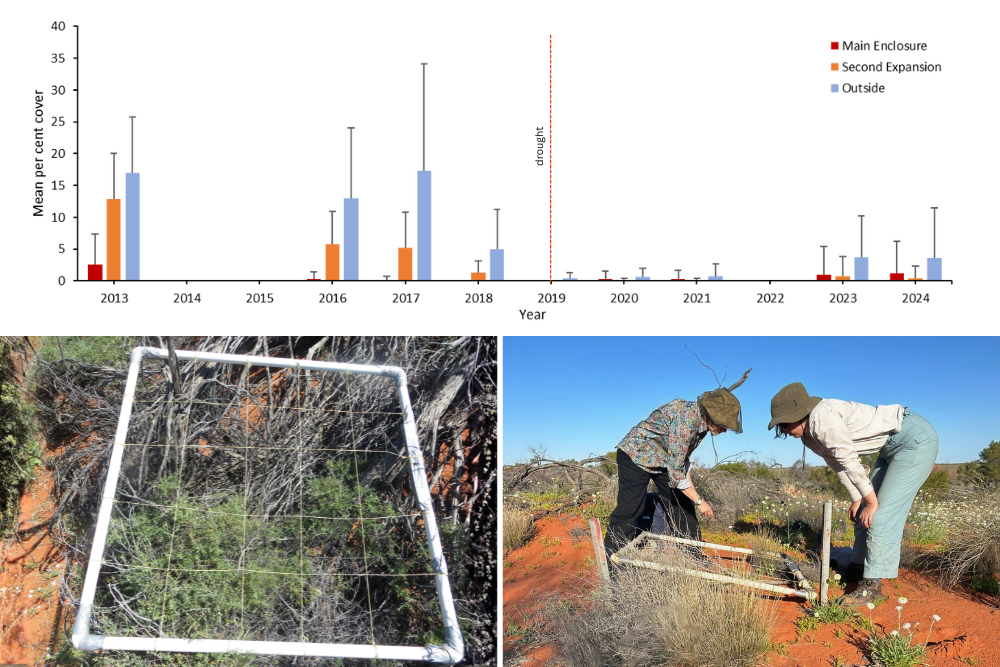

Ruby saltbush (Enchylaena tomentosa) (bottom left) are monitored annually using quadrats to estimate cover (bottom right). We found that ruby saltbush cover was lower inside the reserve compared with outside (above).

Ruby saltbush (Enchylaena tomentosa) (bottom left) are monitored annually using quadrats to estimate cover (bottom right). We found that ruby saltbush cover was lower inside the reserve compared with outside (above).

Arid Recovery has monitored these changes for over two decades through annual cage trapping to estimate population size, quarterly track counts to measure activity in each paddock, and vegetation surveys to investigate impact on their preferred food and changes inside and outside the reserve. These long-term datasets provide the evidence needed to step in when intervention is required.

Over those 20 years, a range of management strategies were tested. One-way gates allowed bettongs to disperse beyond the paddocks they were in, and animals were relocated outside the Reserve. Predator-awareness training was even trialled to help them recognise feral cats. However, while innovative, none of these approaches solved the underlying problem.

Then in 2017, everything changed.

Quolls to the rescue

The turning point came in 2017 when western quolls were reintroduced to Arid Recovery. Scat analysis confirmed that bettongs were a favoured food source for quolls, particularly in drier years when small mammals are scarce. As the quolls settled in, bettong activity declined, with a clear demonstration that natural predator-prey balance was returning to the system.

Look closely and you can see a western quoll on the back of a burrowing bettong

Look closely and you can see a western quoll on the back of a burrowing bettong

A living laboratory

To properly assess the impact of quolls on the ecosystem, we kept them out of one area: the Main Exclosure. Apart from a few curious individuals that had to be moved out, the Main Exclosure has remained quoll-free since 2017. This decision has allowed for a rare ecosystem-scale experiment to see in real time how a native predator reshapes an ecosystem. Bettong numbers remain stable in paddocks with quolls, and in the Main Exclosure, bettongs continue to grow beyond sustainable levels.

That is why, following high track counts and the results of our annual cage trapping in May this year, Arid Recovery relocated 141 bettongs from the Main Exclosure into the Northern and Dingo Paddocks. Moving animals into areas with quolls has helped restore balance and protect sensitive vegetation while still maintaining a healthy bettong population across the Reserve.

Large wildlife populations might seem like a conservation success story, but sheer numbers alone don’t guarantee ecosystem health. When one species becomes overabundant, it can throw the system out of balance, leading to overgrazing, habitat damage, and the decline of other native plants and animals. True recovery means allowing species to thrive as part of a functioning, balanced ecosystem, where predators and herbivores coexist and landscapes can sustain themselves over the long term.

We extend a warm thank you to our staff, supporters, and the volunteers who assisted with this year’s relocation, including participants from the Global Leadership Foundation. This work is physically demanding and logistically complex, but it’s worth every effort to help rebuild a functioning ecosystem.

Arid Recovery bettong wranglers about to head out for a big night of bettong trapping. All animal trapping and handing is performed by trained ecologists under wildlife ethics approval.